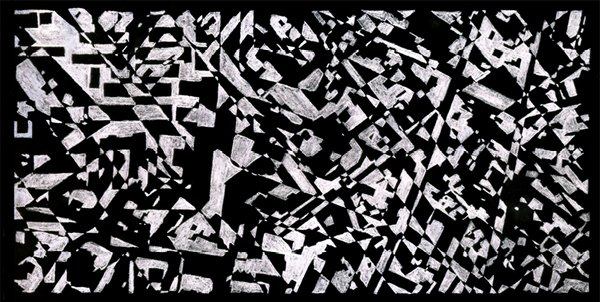

Visual Description: Hand drawing, ink on paper, 40 x 60 [inch]. Lines are drawn from the center to faceted outlines, creating a web of various densities. All individual shapes are tied together at the edges, creating on large fabric. The drawing represents the idea of a centerless city.

THIS IS NOT A NEW CITY [ CITY CONDITIONS ]

2012 // THESIS PROJECT / PART ONE // AARHUS SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE [DK]

[ C I T Y C O N D I T I O N S ]

[ Paris, part two ] [ Aarhus, part three ] [ The Model, part four ] [ Manifesto ]

In City Conditions I’m attempting to build an understanding of what public space is, in order to reconstruct the city condition, the most important aspect of any city.

Whose space is it?

When you exit your front door, you enter the public domain, this is not a neutral zone where anyone can act in a manner they please; here there are rules. Within our society, we have established very clear rules of behavior in the public domain, and breaking them comes at a price. You will be an outcast in the vast flux that is public space, you will be looked at askance by your fellow citizens. In search of where these rules are rooted, we need to take a look at the public domain, public space. One could start by contemplating where the private domain ends and the public begins.

We use public space to communicate with one another, in various ways, in shaping it, marks, and prints. But who has the right to make statements? And what can one state? In New York [ July of 2008 ] I found a piece of street art questioning a budgetary decision made by the U.S. Department of the Treasury, but this was an illegal statement, as it was put there without permission. At another place in the city, there was a huge banner, about four stories high, stating “Life is short. Have an affair in New York” depicting a woman in the process of removing a man’s pants, inciting adultery. This is legal, as the dating site, for which it advertises, has paid for this spot on the wall. From this, one can conclude that you will need capital to get your message across in the public domain, belonging to all of us, this space is ruled by market forces, with very little freedom of personal expression. The public domain becomes a battlefield, wherein the battle for free speech is fought between the advertising companies and the street artists.

Where’s the threshold?

Glass enables us to make a territorial distinction between space but with a seamless, invisible border. In Rue Franklin Apartments, August Perret for the first time liberated the facade from its structural burden and transferred the load to a number of columns, this system was later perfected by Le Corbusier in the Domino system; in the most extreme circumstances, the facade can be seen as purely decorative. This paved the way to the glass house. We put our lifestyle on display in the glass houses, but as soon as we return, the curtains are drawn. We are not comfortable with the idea of being watched. Only when we lose our inhibition, can we show the world how we feel.

The glass house seems to be an attempt to break down the barrier between public and private, but it does so only in the act of bringing the spaces together visually. Often, no thought has been given to the relation of space, it becomes a very black-and-white separation. Sou Fujimoto argues that there should be a variety of spaces between the notion of public and private; “In ordinary architecture, our world is clearly arranged accordingly to the word ‘function’, as is divided into black and white. But isn’t real life sustained by the innumerable acts that lies between them?”. Glass can play a part here, but in order to reach the true potential of this situation, a whole variety of materials must come together.

We are all consumers of public space. Every day we move through it. “The spaces through which we go daily are provided for by locations; their nature is grounded in things of the type of buildings. (...) This is why building, by the virtue of constructing locations, is a founding and joining of spaces.” This means that public space is totally dependent upon the built environment and can, therefore, only exists in the city, the urban environment.

Arnold Reijndorp and Maarten Hajer introduce the term “parochial realms” into the discourse regarding public space. At a DAC lecture, Arnold Reijndorp explained the term as not to be understood in the sense of a church, but rather as a space used by a certain group, defined by lifestyle or ancestry, etc. It is not a place, it is not a certain square. A square can be a parochial realm, but it is not necessarily a fixed place in the city. A parochial realm is not a strong community, it consists of people that recognize each other as being part of the same group. They see the public domain as an interconnected system of parochial realms.

According to Martin Heidegger, space is something that has been made room for, something which starts at a boundary, i.e. dwelling comes from the notion of the cave. By solidifying public space, the air, surrounding our buildings, I arrive at a psychical translation of the built environment as space cleared for dwelling, even if dwelling does not occur. The cities in question are those of the Western world; I do not include the rapidly growing cities of Asia and Africa, as they go through a different evolution. I have located three different city structures, the grid [New York], the medieval city [Paris], and the ring city [Moscow]. I apply the method to the ground floor of each city and then proceed to superimpose these structures on top of one another. Moving from plan to section, I perform the violent act of the section to the superimposed cities; hereby creating a mastersection of the masterplans.

We need to think of public space, the public domain, as a vast emptiness waiting for us to benefit from it by programming it in accordance with our needs. The programming can be of very different nature, some can be for hours, even minutes while others may last for decades.

Dissecting space.

Gordon Matta-Clarks building dissections of the seventies were, among many things, a reaction to social conditions. In these, he developed a method that could be applied to the issue of public space. The strategy is to work with an existing neighborhood group and to involve them in converting the all too plentiful abandoned public space into social space.

This method includes the people of the neighborhood, and in some aspects, it’s about creating public realms. When the method is truly successful it will create a place to stimulate the curiosity of others, making way for open networks for them to join.

We use public space to communicate with one another, in various ways, in shaping it, marks, and prints. But who has the right to make statements? And what can one state? In New York [ July of 2008 ] I found a piece of street art questioning a budgetary decision made by the U.S. Department of the treasury, but this was an illegal statement, as it was put there without permission. At another place in the city, there was a huge banner, about four stories high, stating “Life is short. Have an affair in New York” depicting a woman in the process of removing a man’s pants, inciting adultery. This is legal, as the dating site, for which it advertises, has paid for this spot on the wall.

Visual Description: Digital photograph, through a wall of floor-to-ceiling windows two people are seen embracing in a romantic manner with all the lights on in the apartment.

Visual Description: Hand drawing, pencil on paper; 420 x 297 [mm]. Tracing my movement around the school shows that on a daily basis, I move not only in the xy-plan but also extensively on the z-axis.

Visual Description: In drawing I have superimposed characteristic extracts of three different scales of city development, in regards to public space; the large scale, New York, medium or mixed scale, Moscow and small scale, Paris. These outtakes are superimposed onto an extract of Aarhus, where the condition I am seeking exists: the ambiguous space at the ‘intersection’ of the apartment-block [large scale], the terraced house [medium scale] and the private villa [small scale]. This superimposition leaves me with several guidelines from which to redraw the city.

Visual Description: Drawing pencil on tracing paper; 280 x 135 [mm]. Superimposition of plans from, New York City, Moscow, Paris, and Aarhus. By inverting the drawing the spaces seem to be excavated from the mass, and at some point the drawing turns into a map; a highly fragmented map, with parallels to the cut-up method. It is no longer small figures or objects, but a condition, every space relates and depends upon its neighbors.

The New York grid, is probably the most renown masterplan, familiar to everyone, architect or not. The grid thrives on intersections, the streets crossing the avenues, here is an explosion of life. It is very much two systems, the pedestrian sidewalk dominating the streets and the huge car-lanes dominating the avenues, penetrating each other. The interlinking structure of the pedestrian system dealing with the corners are expressed in the wrapping of the MDF. The streets hitch into the system of avenues. 5 mm dowels stick penetrate the two systems horizontally, interlocking them.

The public space of Moscow is divided into two, I will refer to as the outer- and inner-system. The outer-system consists of big roads - a boulevard system, massive, wide roadways - whilst the inner-system is almost a bazaar like system of spaces moving in between the building mass. They affect each other, and are interlinked; in the model this is illustrated by U-shaped welding rods, almost dragging the spaces into each other. The crossing from the outer- to the inner-system is communicated as a slight touch of the two. The inner-system, in this model, has a lot of similarities with the actual built environment if perceived as a figure ground organization.

Paris, inside la périphérique, the birthplace of the flânuer, here the streets twist and turn. They are old, have undergone numerous transformations, but it is still the medieval ‘city-pace’ that dominats; it is the city as landscape. This is a city designed for people, not cars. The streets are alive, they seem to flow in and out of each other. Suspended from the streetscape are the inner courtyards, small pockets of public space, some accessible from the street, some hidden in the building mass. These courtyards are sometimes almost at the edge of transformation and join the street flow, creating a new shortcut.

According to Martin Heidegger, space is something that has been made room for, something which starts at a boundary, i.e. dwelling comes from the notion of the cave. By solidifying public space, the air, surrounding our buildings, I arrive at a psychical translation of the built environment as space cleared for dwelling, even if dwelling does not occur. The cities in question are those of the Western world; I do not include the rapidly growing cities of Asia and Africa, as they go through a different evolution. I have located three different city structures, the grid [New York], the medieval city [Paris], and the ring city [Moscow]. I apply the method to the ground floor of each city and then proceed to superimpose these structures on top of one another. Moving from plan to section, I perform the violent act of the section to the superimposed cities; hereby creating a mastersection of the masterplans.

This is an attempt at of bringing the cut-up method, developed by Bryan Gysin and perfected by William S. Burroughs, into the realm of architecture. The method reveals and creates new connections in the urban fabric of the cities; both within the three cities and between them. They inform and learn from each other, from this arise spatial qualities and events one could not have predicted. In order to shift from the plan to the section, the models have been superimposed and then cut, hereby creating a section. The models have then been stacked on top of one another, turning the masterplan into the mastersection. Here the mass is not building, but public space, and the gap between the actual psychical mass of the city.